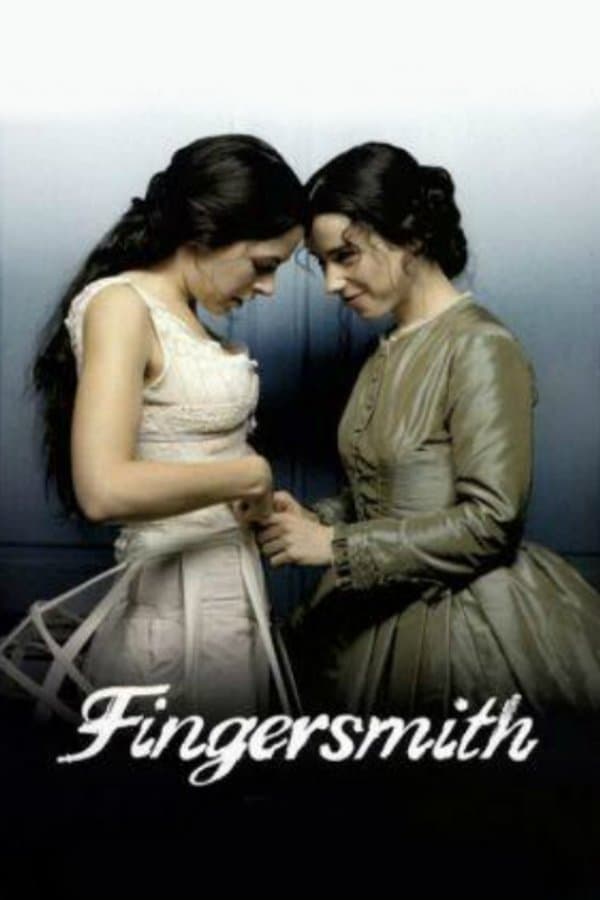

Fingersmith

2005 • Crime, Drama, Mystery • NR

A young woman is hired as a maid to an heiress who lives a secluded life on a large countryside estate with her domineering uncle. But, the maid has a secret: she is a pickpocket recruited by a swindler posing as a gentleman to help him seduce the heiress to elope with him, rob her of her fortune, and lock her up in a madhouse. The plan seems to proceed according to plan until the women discover some unexpected emotions.

Why you should read the novel

Reading Sarah Waters’ novel, Fingersmith, provides a uniquely immersive dive into the complex world of Victorian London that no screen adaptation can fully capture. The novel offers readers intricate layers of character development, exploring the inner lives and motivations of Sue and Maud in ways only the written word can achieve. Waters’ evocative prose pulls you into the gritty streets, the oppressive mansions, and the tense emotional landscapes that form the heart of this compelling story.

By turning the pages of Fingersmith, you’ll encounter rich subplots and subtle hints that add suspense and depth, allowing you to piece together secrets and betrayals alongside the protagonists. Waters’ talent for narrative misdirection unfolds more gradually in print, transforming the reading experience into a satisfying journey of discovery. You’re not just witnessing events—you’re invited to think, question, and empathize at every turn, creating a much deeper engagement.

Choosing the novel over the TV series means engaging with the original vision and tone of Waters’ tale. Her blend of historical detail, psychological complexity, and exploration of sexuality and identity resonates more profoundly within the book’s immersive and unhurried pacing. To truly understand and appreciate the story in its fullness, make the novel your first stop before any adaptation.

Adaptation differences

While the 2005 TV adaptation of Fingersmith is faithful to the source in many ways, several notable differences mark the transition from page to screen. The adaptation necessarily condenses many subplots and secondary characters, streamlining the intricate novel to fit the constraints of a miniseries format. Consequently, some of the nuanced explorations of class, sexuality, and psychological turmoil that Sarah Waters so carefully builds are either minimized or omitted entirely, altering the emotional resonance for viewers.

The television version tends to emphasize the thriller elements and external plot twists, sometimes at the expense of the slow-burning suspense and internal reflections found in the book. For example, Sue’s and Maud’s alternating perspectives, which provide deep insight into their motivations and shifting perceptions, are less pronounced on screen. This means viewers miss out on the subtle ironies and misunderstandings that drive the novel’s most impactful revelations.

Furthermore, the adaptation changes or simplifies certain plot points, especially those related to minor characters and their relationships. Scenes are often visually striking but lack the complexity and ambiguity that the written version delivers, particularly in conveying Maud’s emotional state and background. These changes affect the pacing and tone, making the story at times feel more like a typical period drama than the subversive, layered narrative Waters intended.

Finally, the resolution and emotional closure in the TV adaptation differ in depth and nuance. Where the novel ends on a more ambiguous and introspective note, allowing readers to grapple with the future of the protagonists, the screen version opts for a more definitive and arguably more optimistic conclusion. This choice changes the lasting impression of the story, offering certainty where Waters preferred complexity and open questions.

Fingersmith inspired from

Fingersmith

by Sarah Waters