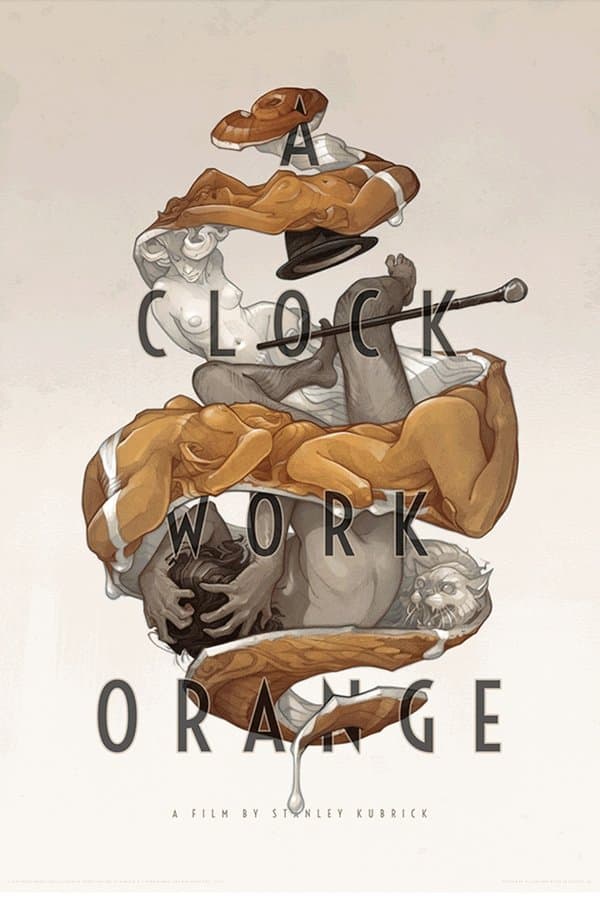

A Clockwork Orange

1971 • Crime, Science Fiction • NC-17

In a near-future Britain, young Alexander DeLarge and his pals get their kicks beating and raping anyone they please. When not destroying the lives of others, Alex swoons to the music of Beethoven. The state, eager to crack down on juvenile crime, gives an incarcerated Alex the option to undergo an invasive procedure that'll rob him of all personal agency. In a time when conscience is a commodity, can Alex change his tune?

Runtime: 2h 17m

Why you should read the novel

Immersing yourself in Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange grants you access to the raw, unfiltered imagination and linguistic innovations that the author carefully constructed. The novel is celebrated for its inventive use of language, known as 'Nadsat,' immersing readers directly into the mindset and culture of its protagonist, Alex. This distinct narrative voice creates a richer, more intimate experience than what any visual adaptation can convey.

Reading the book allows you to explore Burgess’s philosophical and ethical questions in their original context. His commentary on free will, morality, and the nature of evil is deeply woven into the narrative, offering more subtlety and complexity than the film. Readers can reflect at their own pace, considering these provocative themes with the depth and nuance they deserve.

Finally, the novel’s conclusion diverges significantly from the film, providing additional layers of meaning and hope that are lost in the adaptation. By choosing the book over the movie, you are rewarded with a fuller appreciation of Burgess’s intended message and a more thought-provoking, transformative literary journey.

Adaptation differences

One of the most significant differences between Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation and Anthony Burgess’s original novel lies in the use of language. While the movie incorporates some of the 'Nadsat' slang created by Burgess, it relies far more heavily on visuals and performance to express Alex’s world and mindset. As a result, viewers miss out on the immersive, first-person narration and linguistic creativity that define the reading experience and deepen understanding of Alex's character.

Another major difference is the omission of the novel’s final chapter in the film adaptation, at least in its original American releases. In Burgess’s book, the last chapter depicts Alex making a genuine, voluntary move away from violence, suggesting the possibility of personal growth and redemption. Kubrick’s film, however, ends on a much darker note, largely maintaining Alex’s antisocial tendencies and leaving the audience with a sense of cynicism.

The motivations and morality of key characters are more nuanced in the novel than in the film. Burgess offers more inner commentary and development for Alex, providing readers with a deeper understanding of his psychological state and the world that breeds his violence. The adaptation, while visually compelling, often simplifies these motivations to increase dramatic effect, sacrificing the depth and ambiguity present in the book.

Lastly, the treatment of broader social and political themes is more sophisticated in the novel. Burgess delves extensively into the questions of free will, state power, and the ethics of rehabilitation. The film touches on these ideas but ultimately prioritizes shocking visuals and style over sustained, nuanced philosophical engagement. As a result, the book provides a richer exploration of its dystopian world, encouraging more thoughtful consideration of its underlying issues.

A Clockwork Orange inspired from

A Clockwork Orange

by Anthony Burgess